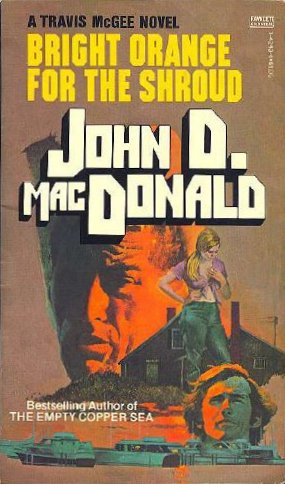

“Now, of course, having failed in every attempt to subdue the Glades by frontal attack, we are slowly killing it off by tapping the River of Grass. In the questionable name of progress, the state in its vast wisdom lets every two-bit developer divert the flow into drag-lined canals that give him ‘waterfront’ lots to sell. As far north as Corkscrew Swamp, virgin stands of ancient bald cypress are dying. All the area north of Copeland had been logged out, and will never come back. As the glades dry, the big fires come with increasing frequency. The ecology is changing with egret colonies dwindling, mullet getting scarce, mangrove dying of new diseases born of dryness.” ― John D. MacDonald, Bright Orange for the Shroud (1965)

Florida Authors

Tennessee Williams in Key West

“I went down to Key West because I love swimming . . . It was January, and I had to go someplace where I could swim in the winter so I came down here because it was the southernmost point, and I was immediately enchanted by the place. It was so much more primitive in those early days.” – Tennessee Williams (1911-83), quoted in Pop Culture Florida (2000) by James P. Goss

“Williams chose Key West as the first place to settle down after his newfound fame. A visitor to the island in 1941, he moved there after Glass debuted on Broadway and lived briefly at the La Concha Hotel, where he is thought to have finished the first draft of another highly personal play, A Streetcar Named Desire, set in New Orleans. In 1949, he bought a home at 1431 Duncan Street, the only residence he would ever own outright.” – Florida Artists Hall of Fame Bio

“Tennessee Williams visited and lived in Key West from 1941 until his death in 1983. It is believed that he wrote the final draft of Street Car Named Desire while staying at the La Concha Hotel in Key West in 1947. He established residence here in 1949 and in 1950 bought the house at 1431 Duncan Street that was his home for 34 years. He was part of the literary movement that resulted in Key West and the Florida Keys being recognized as the cultural and historical location it is today.” – Tennessee Williams Museum Bio

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

“We cannot live without the earth or apart from it, and something is shrivelled in a man’s heart when he turns away from it and concerns himself only with the affairs of men.” ―Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Cross Creek (1942)

Only One Day

“Today is only one day in all the days that will ever be. But what will happen in all the other days that ever come can depend on what you do today.” – Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls, 1940

A River of Grass

“There are no other Everglades in the world. They are, they have always been, one of the unique regions of the earth, remote, never wholly known. Nothing anywhere else is like them; their vast glittering openness, wider than the enormous visible round of the horizon, the racing free saltness and sweetness of the their massive winds, under the dazzling blue heights of space. They are unique also in the simplicity, the diversity, the related harmony of the forms of life they enclose. The miracle of the light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slow-moving below, the grass and water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades of Florida. It is a river of grass.” —Marjory Stoneman Douglas, The Everglades: River of Grass, 1947

Donn Pearce

Donn Pearce wrote the 1965 novel Cool Hand Luke, which was loosely based on the two years he spent on a prison road gang. This fact alone makes him cooler than any of us. After Pearce sold the movie rights to Warner Bros. for $80,000, the novel was turned into a classic 1967 film of the same name directed by Stuart Rosenberg and starring Paul Newman in the title role of “Lucas ‘Luke” Jackson” (his signature role in my opinion). The film also starred Strother Martin (“Captain”), Harry Dean Stanton (“Tramp”), Dennis Hopper (“Babalugats”), Ralph Waite (“Alibi”), Wayne Rogers (“Gambler”), Anthony Zerbe (“Dog Boy”), Richard Davalos (“Blind Dick”), Joe Don Baker (uncredited as “Fixer”), Jo Van Fleet (Luke’s mother, “Arletta”) and Joy Harmon (“The Girl”). Pearce himself made a cameo in the film as a convict known as “Sailor.” Although he co-wrote the script (for an additional $15,000) with screenwriter Frank Pierson (Dog Day Afternoon), Pearce absolutely hated the movie. “I seem to be the only guy in the United States who doesn’t like the movie,” Pearce told the Miami Herald in 1989. “Everyone had a whack at it. They screwed it up 99 different ways.” For example, Pearce thought that Newman was totally wrong for the part. In addition, it was actually Pierson who added the famous line, “What we’ve got here is failure communicate,” to the script. However, Pearce argued that the “redneck” Captain would never have had such a word in his vocabulary. The line later turned up in two Guns N’ Roses songs: “Civil War” from Use Your Illusion II (1991) and “Madagascar” from Chinese Democracy (2008). George Kennedy ended up winning a “Best Supporting Actor” Oscar for his amazing performance as “Dragline.” Newman was nominated for a “Best Actor” Oscar, but lost out to Rod Steiger for In the Heat of the Night. Pearce and Pierson were also nominated for a “Best Screenplay” Oscar, but lost out to Stirling Silliphant for In the Heat of the Night. Most of the filming itself took place not in Florida but in Stockton, California. The infamous boxing scene between Luke and Dragline took three days to shoot. Stanton taught Newman how to play “Plastic Jesus” on the banjo. Believe it or not, Telly “Kojak” Savalas was initially tapped to play Luke, but he was filming The Dirty Dozen in Europe at the time (Jack Lemmon also briefly considered for the role!). In addition, Bette Davis turned down the role of Arletta that went to Jo Van Fleet.

Donald Mills Pearce was born on September 28, 1928, in Croydon, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. After dropping out of high school in the 10th grade and serving in the United States Army during World War II (he lied about his age to join up and then went AWOL), followed by a stint in the Merchant Marine, Pearce got involved in counterfeiting, safecracking and burglary. In 1949, he was arrested in Tampa for attempting to rip off a movie theater and served two years hard labor on a Florida chain gang, mostly at the Tavares Road Prison in Lake County (which he labeled “a chamber of horrors”). It was here he heard about the legend of “Cool Hand Luke,” who was killed during a prison escape attempt. In a 2005 interview with the Sun Sentinel, Pearce remarked, “I never knew Luke … He was a legendary con, famous for escaping. I did know the walking boss who shot him. I put all these stories together. I mixed legends and used myself as a model. The real Luke never bet the guards he could eat 50 hard-boiled eggs. That was me. They called off the bet after they saw how much I could eat.” Pearce later lived in Fort Lauderdale and supplemented his writing efforts over the years with work as a bail bondsman, private investigator and bounty hunter (AKA “skip man”), as well as freelance journalist, writing for the likes of Playboy, Esquire and Oui. Pearce was also friends with literary outlaw Harry Crews (A Feast of Snakes). He and his wife Christine raised three sons in South Florida. Pearce’s other works include Pier Head Jump (1972), Dying in the Sun (1974) and Nobody Comes Back (2005), a novel about the Battle of the Bulge during World War II. According to Pearce in the 2005 Sun Sentinel interview, “The world really isn’t evil, it’s just dumb … There’s no cure for dumb. Dumb will outsmart you.”

Leicester Hemingway

Born on April 1, 1915, in Oak Park, Illinois, Leicester Clarence Hemingway was sixteen years younger than his famous brother, Ernest, and lived in the shadow of the literary legend his entire life. However, by all accounts, Leicester idolized his older brother and eventually became a respected writer in his own right. Ernest nicknamed his little brother, “the Baron.” In 1953, Leicester published his first novel, The Sound of the Trumpet, which was loosely based on his wartime experiences in France and Germany during World War II. In 1962, Leicester published the critically acclaimed biography, My Brother, Ernest Hemingway.

Believe it or not, Leicester founded his own micronation called the “Republic of New Atlantis” (actually an eight-foot-by-30-foot barge located just 12 nautical miles off the coast of Jamaica) in 1965. Stating that “there’s no law that says you can’t start your own country,” Leicester even created a New Atlantis flag, issued New Atlantis postage stamps, and created New Atlantis currency. Unfortunately, New Atlantis was completely destroyed during a tropical storm the following year. An active outdoorsman like his brother, Leicester frequently fished off the coast of Bimini and even published a monthly newsletter, The Bimini Out Islands News. He even appeared on a 1980 episode of In Search of … titled “The Bimini Wall.” Faced with several debilitating health issues, Leicester died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in his Miami Beach home on September 13, 1982, at the age of sixty-seven.

On Ernest’s Life

“Ernest lived as he died—violently. He had a tremendous respect for courage. During his own lifetime he traded in it, developed it, and taught other people a great deal about it. And his own courage never deserted him. What finally failed him was his body. This can happen to anyone.”

On Havana

“Havana is one of the loveliest, wickedest, most mysterious and enchanting cities in the world.”

On Robert Capa

“Robert Capa had come to Spain via central Europe as a photographer. He went where Ernest went, drank where Ernest drank, made jokes that made Ernest laugh, and generally proved himself one hell of a fine fellow.”

On Ernest’s Drinking Prowess

“Ernest was then drinking fifteen to seventeen Scotch-and-sodas over the course of a day. He was holding them remarkably well.”

On Ernest’s Love of Cats

“Much as been written about Ernest’s enormous fondness for cats. He claimed they were superior to people of unknown quality. ‘A cat has absolute emotional honesty, Baron,’ he told me once. ‘Male or female, a cat will show you how it feels about you. People hide their feelings for various reasons, but cats never do.'”

Ernest Hemingway Home & Museum

Built by 1851 by Asa Tift, a captain and ship’s architect, the house (the single largest residential property on the island) was bought by Ernest “Papa” Hemingway and his second wife, Pauline, in 1931 at a cost of $8,000 (it was actually a wedding gift from Pauline’s wealthy uncle, Gus). The couple lived there with their two sons, Patrick and Gregory (Ernest divorced Pauline in 1940 and married Martha Gelhorn three weeks later). Hemingway reportedly wrote the final draft of A Farewell to Arms, as well as classic short stories such as “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” at the house. He created a writing studio in the second floor of a carriage house on the property that was connected to the master bedroom by a walkway. A boxing aficionado, Hemingway built a ring in the backyard where he often sparred with local fighters. An in-ground, saltwater pool was added in 1938 at a cost of $20,000. Hemingway hired his friend and handyman Toby Bruce to build a high brick wall around the house as privacy from tourists anxious to catch a glimpse of the famous writer. Hemingway also hauled away a urinal from Sloppy Joe’s Bar to the house and turned it into a fountain in the yard. Approximately 40 to 50 polydactyl (six-toed) cats currently live on the grounds of the Hemingway Home. According to legend, the cats are descendants of Hemingway’s own six-toed cat, Snowball (however, Patrick has denied that his father owned any cats in Key West, only at his residence in Cuba, Finca Vigia). Designated a National Historic Landmark, the Ernest Hemingway Home is located at 907 Whitehead Street (across from the Key West Lighthouse).